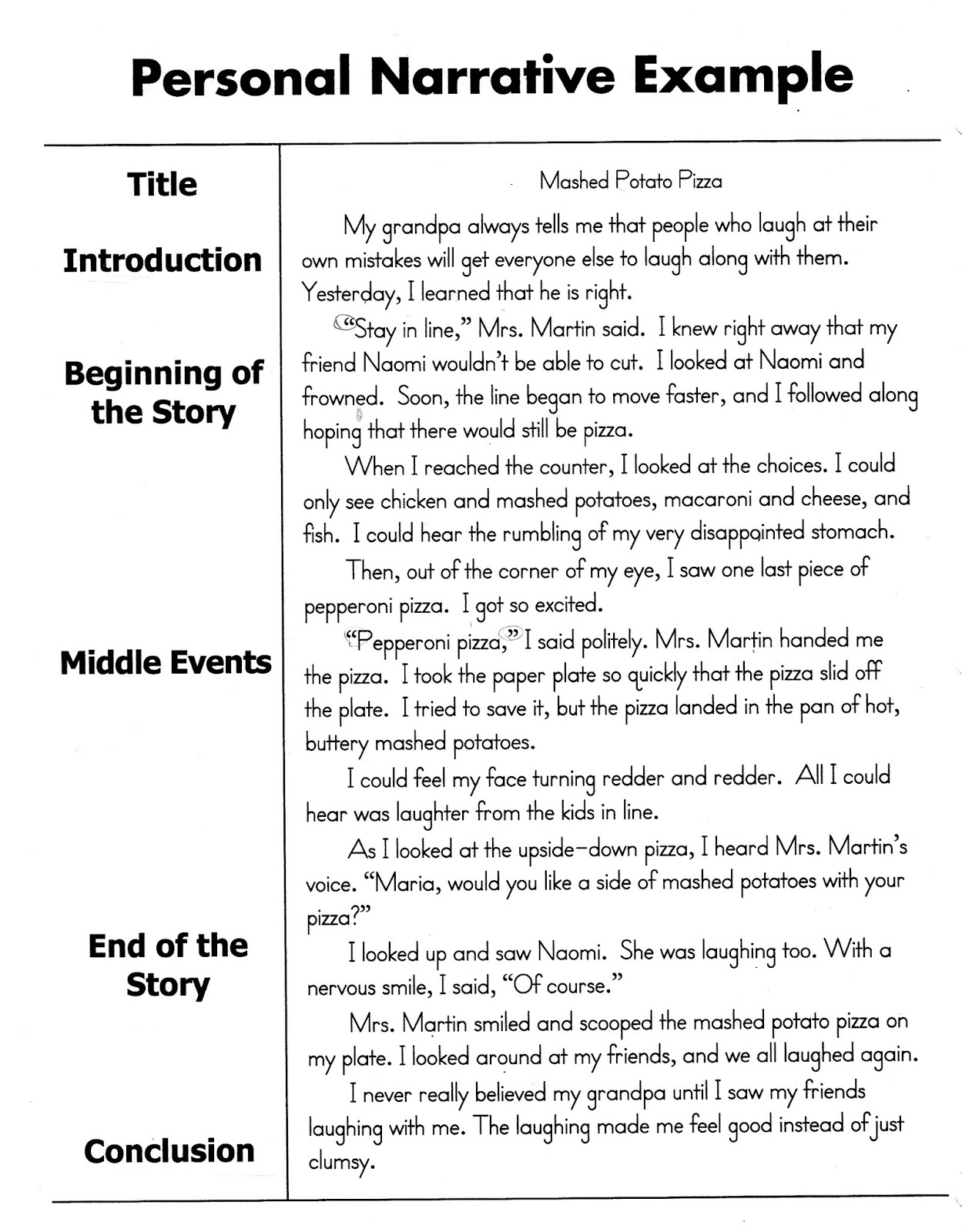

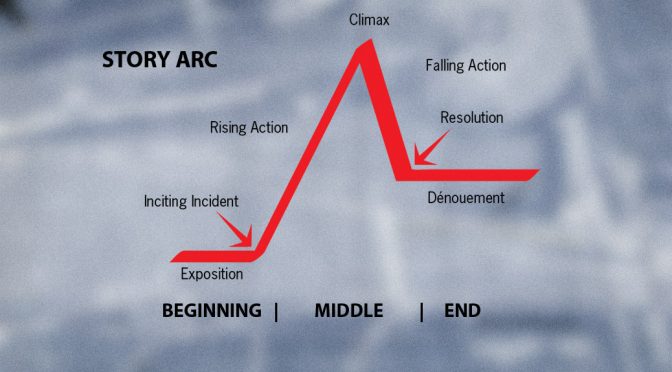

The essence of good first-person narrative is sharing an experience, letting the reader see and feel it, and reaching a resolution from which both reader and writer grow or have an ‘aha’ moment. Writers often confuse essays with a recollection of an event — they fail to share how the experience enlightened them, affected them, changed their opinion. An essay is an internal journey of discovery. To work well, the reader takes that journey with you.

What to write

The topics are endless. Almost anything can be the subject material for an essay — nature, climbing, sailing, death, parenting, relationships — but ask yourself what you feel passionate about, or what you have experienced that has universal appeal. Ask yourself what makes you happy, or what makes you sad. When you have a clear idea of what you’d like to share, begin a draft.

The draft

The draft essay is the first step in clearing your head for a final, tightly focused piece. Don’t hold back in your draft, don’t critique it, just let your emotions and thoughts run unchecked. Write where you are comfortable; perhaps try longhand if you usually type. Then, when you think you’ve said all you can say, close the file or notebook and walk away.

When you’re ready, perhaps in a day or so, read your draft. You’ll find paragraphs that make you wince, and others that shine with brilliance. You might find you sound dogmatic or overly emotional. It’s good to recognize this now before you submit your piece. If you don’t, the editor will.

Many essays for commercial publications are not lengthy — perhaps 1,000 to 1,200 words, often less. To share all you want to share, you must keep focused on three elements — the beginning or hook; the conflict or the internal journey; and the ending, what you find at your destination.

1. The hook

Look at your first draft and see what parts of it are crucial to set the scene — people, places, events — and what will distract the reader with unnecessary detail. The balance lies in giving the reader enough information so they can know you at least a little. Remember, your neighbors, spouse and children may be familiar with you and your experience, but your readers are not, yet are about to embark on an intimate journey with you. On the other hand they don’t want tedious details about your Aunt Marge or her canary, unless they’re coming on the journey too.

The most successful essay I’ve published had this introduction:

I sob in Sydney International Airport as my 5-year-old daughter Bee and I bid our friends and family an emotional farewell. At age 30, I am leaving my native Australia, after a whirlwind romance, to join my husband in his native Minnesota.

Immediately, the readers (Minnesota Monthly) knew they were going to hear about a physical journey as well as the internal one, and the key players were myself, my daughter and husband, and a relocation to Minnesota.

What wasn’t important in this piece is what got to me the airport — why my daughter and I were going to Minnesota, and not my husband to Australia, or whatever. What mattered was that I was at the airport, and that I was leaving.

If you are writing about coping with infidelity, don’t talk about the ten good years before your ex-spouse’s affair; start from when you discovered the betrayal.

In short, begin with the phone call, the letter, the diagnosis, the news, and the event… not what led up to it.

2. The journey

We’re packed, ready and off we go. This is where we experience your challenge or conflict with you, grapple with the curveball, struggle to make sense or laugh or cry with you. To recapture your emotions and make us feel them, the body must be lively and interesting. Again, don’t bog down your story with unwieldy descriptions; keep focused on your emotions and the drama to keep the reader moving forward. Make sure you occasionally remind of us of the theme of the journey, but succinctly.

It’s OK to pause, recollect your thoughts, or comment on where you thought this journey may have led you, but you do have to press on. You’ve taken us this far and we’re engrossed, so you have an obligation to see us to the end.

3. The destination

Aah, so we discover that it is possible to survive a Minnesota winter; a broken heart; beat the odds; or change a belief about yourself. Tie the ends together, remind us where we were when the journey began and how far we’ve come. The ending or resolution doesn’t have to be happy, but there should be evidence of growth or a new understanding in the author.

And if the reader can apply that growth and understanding to his or her own life, then your essay has achieved its goal — a journey worth taking.

Editing your essay

Now for the hard work! You’ve written what you think is close to a publishable piece, but don’t be hasty in sending it off. Put this second draft away and then reread it, removing yourself from your experience as much as possible. Look for the following pitfalls:

1. Emotion vs. emotional

It’s fine to be angry, sad or happy. We want those emotions, but remember the reader is more removed from your particular experience. If you are too emotional, you will appear to be venting, possibly irrational and to not have grown from your challenge. If you haven’t grown, neither can the reader.

2. Passive vs. active

There is a tendency for essays to be passive because they describe past events, which offers no immediacy to readers and less chance to engage them. Look at your sentence structure, if you have a lot of “was” or “by” in your essay, revise it. Look at the following:

“I was being lied to by my wife” is passive. So break it down: Who’s doing the action? The wife: the wife is lying. What is the verb or the action word? Lying. Who is having something done to it? I am. Sentence structure should be subject/verb/object: “My wife lied to me” — offering less to wade through and bringing the action (the verb) closer to the reader.

3. Adverbs

Writers often think if they use adverbs they’re heightening emotion when, in fact, the opposite is true. Use of words ending in “-ly” weaken prose. If you shout because you’re angry, the reader should know that from your actions and not be told, “I shouted at her angrily.”

4. Show, don’t tell

Sheila Bender, author of Writing Personal Essays: How to Shape Your Life Experiences for the Page, says that a good essay is one with imagery appealing to the five senses. To engage readers, offer enough detail so the audience sees, smells, hears, etc., what you are describing. Don’t “tell” the reader what’s happening; use verbs that “show.” Don’t say, “it was a hot day,” instead, tell us, “the sun beat down.”

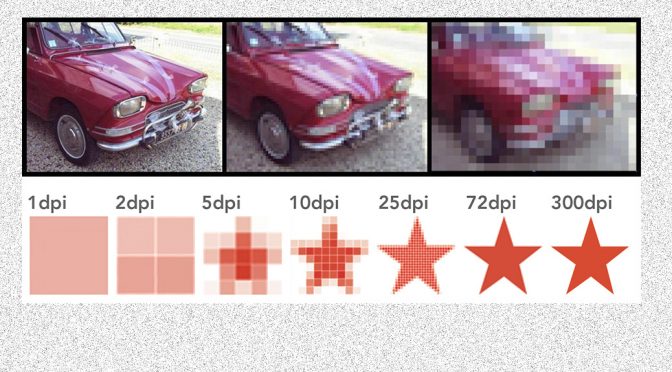

And what about our “high resolution” version of this image (3024 pixels x 4032 pixels)?

And what about our “high resolution” version of this image (3024 pixels x 4032 pixels)?